After the shot landed with a final thud, Gong Lijiao knew her long goodbye was complete. She had just finished her last attempt at her fifth National Games, securing a historic fifth consecutive women's shot put title on Sunday.

But in that moment, the result felt secondary. What followed was a farewell ritual as the 36-year-old Olympic champion walked slowly across the field, shaking hands with and hugging each of her opponents.

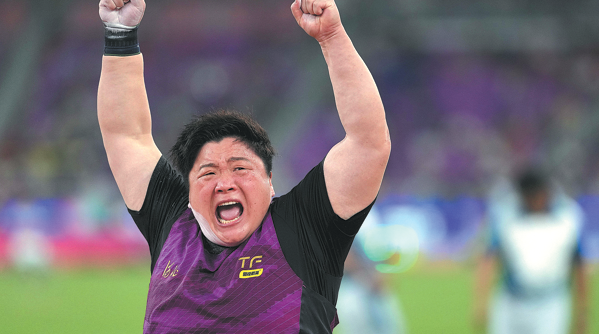

Gong Lijiao lets out a triumphant cheer after putting her last shot into the field, ending a stellar, two-decade career with a history-making fifth consecutive National Games title on Sunday. [Photo/Xinhua]

"I said, 'From now on, it's up to you all,'" Gong recalled after the competition. "I don't really want to leave, but there's no other way. My injuries are already very severe. I've had three injections for the National Games."

THE FOUNDATION

Gong's remarkable career, which saw her remain among the world's elite for nearly 20 years, was built on an almost unimaginable workload. In her youth, the volume of training was staggering.

"When I just turned an adult, the training volume was basically 200 throws a day, 100 in the morning and 100 in the afternoon," she told Xinhua prior to the National Games at a training base in her hometown Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province.

"This was the tradition of Hebei, to build a foundation through sheer, relentless work," Gong explained. "At that time, I could really handle the volume. That stage was about building up this foundation for myself, which is what has allowed me to have such a long athletic career now."

She reflected on the purpose of this grueling routine, explaining that enduring such monotony was essential for forging the muscle memory that defines a champion.

"This kind of boredom probably has to be endured through tens of millions or more repetitions, letting your body develop muscle memory, so you can more fully execute the technique you want," she said.

The conditions of her early training were a world away from modern facilities as she trained through harsh winters outdoors. "It was snowing, and we would wear at most a knitted vest, with short sleeves and shorts, and just train," she said, recalling how the cold was so intense that the ball would freeze to her neck.

"When I first started training as a child, when the calluses got thick, I didn't know to shave them. They would just tear open, bleeding, and I'd wrap them in tape and keep training."

THE ANCHOR

Behind the champion stood a family from Shao Ying Village in Shijiazhuang, whose simple, steadfast love underpinned her resilience. Her parents, former farmers, offered support that was never about technique or distance, but always about character and care. Her mother, an uneducated woman with a warm heart, shaped Gong's easygoing nature.

"My personality comes from her - easygoing, and never holding onto things," Gong said. Her mother's most frequent lesson was about sharing. "She always told me, 'You have to know how to share.' If you bought something to eat, you had to give it to your friends and classmates. You couldn't just think about yourself."

One of her fondest memories involved a comical attempt at a surprise for a Shanghai Diamond League meeting on Mother's Day in 2018, when the organizers secretly flew her mother in.

"But my mother was so funny," Gong recalled with a laugh. "She secretly called me and said, 'Jiao, let me tell you something... They told me not to tell you, but I think I have to! They're having me come to the venue to cheer for you.' She didn't really understand the concept of a 'surprise'. She thought, 'Why wouldn't I tell my daughter I'm coming?'"

On the day, Gong saw staff trying to hide her mother behind a car. "I saw it all," she laughed. The incident, though spoiling the planned surprise, brought Gong a unique sense of comfort. "I felt very reassured that day because I knew I could see her right after the race."

Her father provided the structure, his strictness a form of love that instilled discipline. "His rules were numerous," Gong explained. "Once, as a hungry child, I started tapping my chopsticks on the bowl before everyone sat down. His chopsticks came down 'bang!' on my hand."

He enforced traditional table manners: no talking during meals, no flipping food to pick the best bits, and crucially, "you couldn't take three consecutive bites from the same dish." While Gong resented it as a child, she now sees its value. "Growing up, I'm actually very thankful for my father's strictness. It gave me a basic decorum."

At the heart of the family was a deep, quiet partnership between her parents. "The deepest impression I have is of them going to the hospital. My mother had a lot of health issues, and my father was very healthy. He would always follow behind her, carrying her clothes." Though they bickered like any couple, "when it mattered, my father took especially good care of her."

The ultimate homecoming treat for Gong was her mother's hand-pulled noodles. "She and my father had a great system. She would knead the dough, and he would roll it out with a big rolling pin, fold it, and then cut it," Gong described.

"When I was little, with five or six people in the family, we'd just have one dish, maybe stir-fried potatoes or cabbage from our garden. The most important thing was that bowl of noodles. That was the feeling of home," she added.

THE UPS AND DOWNS

Her first major breakthrough came in 2009 when she shattered the 20-meter barrier with a throw of 20.35m.

"My condition was really excellent, and I felt so full of confidence in myself," she remembered, though the milestone's significance initially escaped her. "Actually, I was a bit dazed on the field, I didn't know what 20.35 meters meant."

Her Olympic journey, however, became a lesson in patience and frustration. At the 2008 Beijing Games, the 19-year-old finished fifth, only to later be upgraded to bronze after medalists were disqualified for doping.

Following a foot surgery in 2011, the same scenario unfolded at London 2012, where her fourth-place finish eventually became a silver. While she ultimately received the medals, the disappointment of never standing on the Olympic podium left an indelible mark.

Her career hit its lowest point at the 2016 Rio Games, where she arrived full of confidence but finished fourth, a result that felt like a devastating step backward.

"I felt the frustration was enormous after Rio 2016," Gong admitted. "I felt like vomiting when I saw the track and field stadium, especially when I saw the shot put, the feeling was even stronger."

Despite winning the World Championships in 2017 and 2019, an Olympic gold remained the ultimate goal. She kept training with a sense of unfinished business. The postponement of the Tokyo Olympics then hit her like a physical blow.

"This year was truly agonizing, especially for someone old like me," she said of the delay, tears welling up at the memory. "I simply couldn't accept it at that moment."

When the Tokyo Games finally arrived, Gong breezed through qualifying in first place with 19.46m, but the night before the final was restless as she slept only four to five hours, with techniques for throwing far spinning in her head.

In the final, her first throw of 19.95m would have been enough to win, yet she felt "somewhat unsettled." Battling the stifling midday sun, she was "so sun-scorched I felt a bit drained."

Then came her trademark late-competition surge. Her fifth throw of 20.53m was a new personal best, making her the only athlete to break 20 meters and finally securing the gold.

"That was when my heart settled," she recalled. But she was not done. On her sixth and final attempt, she unleashed a throw of 20.58m, breaking the personal best she had set just minutes before.

"I think I could have done even better, but I was probably too overwhelmed with emotion. I've waited for this day for too long."

"I've pictured this scene in my head countless times. Being able to achieve it today is truly like a dream," she said, even pinching herself to confirm it wasn't an illusion. "A poor performance is a nightmare; a good one is a beautiful dream. I hope my beautiful dream can last a little longer."

THE FINAL CHAPTER

Yet even at her moment of ultimate glory in Tokyo, the perfectionist in her saw flaws.

"When I look back at the video of my Tokyo Olympics performance, my technique wasn't executed particularly well," she said. This regret, coupled with her enduring love for the sport, fueled her decision to continue, aiming for the mythical 21-meter mark.

The years after Tokyo, however, brought a physical toll that even her resolve could not overcome. Age and a lifetime of accumulation led to a sharp decline.

"Especially after turning 30, my physical fitness and all kinds of bodily functions declined rapidly," Gong admitted. Her training volume dropped from 200 throws a day to 35, which still left her exhausted.

A severe knee injury, a third-degree tear caused by long-term wear and tear, became the defining obstacle of her final chapter.

"Now when I walk, or even sit for a long time, I'll suddenly feel a sharp, stabbing pain," she described. It was a constant companion, a limitation that dictated her every move.

Her days were no longer defined by training sessions alone, but by treatments. "Now, basically, managing one training session a day is my limit, and I spend the rest of my time in the medical room."

This physical reality, compounded by the personal tragedy of her mother's passing, which cast a shadow over her final year, made her decision to retire inevitable.

World Athletics paid tribute to Gong as she retires, recognizing her as "one of the most accomplished shot putters of her era, with a career defined by consistency, longevity and major-championship success."

Through it all, her perspective remained steady. Asked about the transition from being an Olympic champion to now missing podiums, she showed hard-won wisdom.

"To say I'm used to it, I'm actually not; to say I'm not used to it, I kind of am. Why? I think this is what life is - full of great ups and downs," she said. "As long as I've tried my best, I think I have no regrets."

Her motivation to persist long after most would have retired was simple.

"Because I love it, that's why I persist," she said, with the aim of becoming a beacon of hope for young generations. "Light doesn't just shine when it's bright; it should shine even brighter in the darkness. That is the true meaning of light."

As she concluded her final National Games, her thoughts turned to her mother. "This year I experienced the lowest point of my life, including my mother's passing, and my own injuries. I really hope she could be here to share this gold medal with me."

Her final message to the young woman who started this journey 25 years ago was one of gratitude: "Thank myself for never giving up or abandoning the fight."

Share:

Share:

京公網安備 11010802027341號

京公網安備 11010802027341號